Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

Sheetla Mata Mandir Gurugram

The midday sun beat down on Gurugram, a stark contrast to the cool, shadowed interior of the Sheetla Mata Mandir. This wasn't a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a fact that surprised many given its historical and cultural significance. My journey across India to document every UNESCO site had brought me here, to this vital pilgrimage center, driven by curiosity and a desire to understand its enduring appeal. The temple, dedicated to Sheetla Mata, the goddess of smallpox, stands as a testament to a time when disease held a powerful sway over human life. Unlike the ornate and vibrant temples of South India I'd grown accustomed to, Sheetla Mata Mandir presented a different aesthetic. The structure, primarily built from brick and stone, exuded a sense of aged resilience. The lack of elaborate carvings or bright colours initially struck me, but as I spent more time within the complex, I began to appreciate the understated elegance. The simplicity felt purposeful, almost reverential, focusing the attention on the spiritual aspect rather than visual grandeur. The main entrance, a relatively unassuming archway, led into a large courtyard. Devotees, many carrying offerings of cooked food – a unique tradition of this temple – moved with a quiet determination. The air hummed with a low murmur of prayers and the clanging of bells. I observed families sharing meals on the temple grounds, the food having been offered to the goddess and then consumed as 'prasad', a blessed offering. This communal act of eating, blurring the lines between the sacred and the everyday, was a powerful display of faith and community. Inside the sanctum sanctorum, the atmosphere was palpably different. The dimly lit space, illuminated by flickering oil lamps, held an air of mystery and ancient power. The idol of Sheetla Mata, adorned with simple garments and jewellery, was a focal point for intense devotion. I watched as devotees whispered their prayers, their faces etched with hope and reverence. The absence of opulent decoration within the sanctum further amplified the sense of raw, unfiltered faith. The architecture of the temple, while not as visually striking as some of the UNESCO sites I've visited, held its own unique charm. The use of local materials, the simple lines, and the open courtyard all contributed to a sense of groundedness, a connection to the earth. I noticed intricate brickwork in certain sections, showcasing the skill of the original builders. The temple's design seemed to prioritize functionality and accessibility over elaborate ornamentation, reflecting its role as a place of pilgrimage for people from all walks of life. One of the most striking aspects of my visit was the palpable sense of continuity, a bridge between the past and the present. While the temple has undoubtedly undergone renovations over the centuries, the core beliefs and practices seemed to have remained unchanged. This resilience, this unwavering faith in the face of modern advancements in medicine, was a testament to the deep-rooted cultural significance of Sheetla Mata. Leaving the Sheetla Mata Mandir, I carried with me a deeper understanding of faith and its diverse expressions. While not a UNESCO site, this temple offered a unique glimpse into the living history and cultural fabric of India. It served as a reminder that heritage isn't just about grand monuments and breathtaking architecture, but also about the intangible threads of belief, tradition, and community that bind a people together. The experience underscored the importance of exploring beyond the designated lists and discovering the hidden gems that offer a richer, more nuanced understanding of a place and its people.

Agra Fort Agra

Intricate carvings adorn the walls of Agra Fort, a UNESCO World Heritage site erected from 1565 CE, revealing a synthesis of Timurid-Persian and Indian artistic traditions ([1][11]). As one of the earliest surviving buildings from Akbar's reign, the Jahangiri Mahal showcases this blend ([12]). Its exterior elevations follow a predominantly Islamic scheme, while the interiors are articulated with Hindu elements ([7]). Heavily fashioned brackets, a key feature of Akbari architecture, are prominent throughout ([13]). This fusion reflects a broader Mughal approach of incorporating regional artistic styles ([14]). Furthermore, specific motifs rooted in Indian heritage are visible within the fort. The use of carved panels and decorative arches inside the Jahangiri Mahal points to indigenous architectural influences ([15]). While direct connections to specific Vastu or Shilpa Shastra texts for the fort's overall design are not explicitly documented, the architectural vocabulary shows a clear dialogue with pre-existing Indian forms ([16]). The emperor's throne chamber in the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience), constructed by Shah Jahan, features a marble canopy and was originally painted with gold ([17]). Overall, the fort is a powerful expression of Mughal imperial authority, built with red sandstone and later enhanced with white marble by Shah Jahan ([18]). Red sandstone, the primary construction material, lends a formidable presence to the fort, while marble inlays introduced later add refinement ([18]). During the Mughal Period, the fort served not only as a military stronghold but also as a palatial complex, reflecting the empire's grandeur ([19]). Its strategic location on the banks of the Yamuna River further enhanced its importance ([20]). The fort's layout incorporates elements of both Islamic and Hindu design principles, evident in its gateways, courtyards, and residential palaces ([21]). This architectural syncretism reflects the inclusive policies of Mughal emperors like Akbar, who sought to integrate diverse cultural traditions into their imperial projects ([22]). The fort embodies the confluence of Persian, Islamic, and Indian aesthetics, creating a unique architectural vocabulary that defines Mughal architecture ([23]).

Tiruchirapalli Fort Tiruchirapalli

The Rockfort, as it’s locally known, dominates the Tiruchirapalli skyline. Rising abruptly from the plains, this massive outcrop isn't just a fort, it's a layered testament to centuries of power struggles and religious fervor. My lens, accustomed to the sandstone hues of Madhya Pradesh, was immediately captivated by the stark, almost bleached, granite of this southern behemoth. The sheer scale of the rock itself is awe-inspiring, a natural fortress enhanced by human ingenuity. My climb began through a bustling marketplace that clings to the rock's lower slopes, a vibrant tapestry of daily life unfolding in the shadow of history. The air, thick with the scent of jasmine and spices, resonated with the calls of vendors and the chiming bells of the Sri Thayumanaswamy Temple, carved into the rock face. This temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, is an architectural marvel. The intricate carvings, some weathered smooth by time, others remarkably preserved, speak to the skill of the artisans who labored here centuries ago. The sheer audacity of excavating and sculpting such a complex within the rock itself left me speechless. Ascending further, I reached the Manikka Vinayagar Temple, dedicated to Lord Ganesha. The contrast between the two temples is striking. While the Shiva temple is a study in verticality, reaching towards the sky, the Ganesha temple feels more grounded, nestled within the rock's embrace. The vibrant colours of the gopuram, a stark contrast to the muted tones of the rock, add a touch of playful energy to the otherwise austere surroundings. The climb to the Upper Rockfort, where the remnants of the fort itself stand, is a journey through time. The steps, worn smooth by countless pilgrims and soldiers, are a tangible link to the past. As I climbed, I noticed the strategic placement of fortifications, the remnants of ramparts and bastions that once protected this strategic location. The views from the top are breathtaking, offering a panoramic vista of the city and the meandering Kaveri River. It's easy to see why this location was so fiercely contested throughout history, from the early Cholas to the Nayaks, the Marathas, and finally the British. The architecture of the fort itself is a blend of styles, reflecting the various dynasties that held sway here. I was particularly struck by the remnants of the Lalitankura Pallaveswaram Temple, a small, almost hidden shrine near the top. Its simple, elegant lines stand in stark contrast to the more ornate temples below, offering a glimpse into an earlier architectural tradition. Beyond the grand temples and imposing fortifications, it was the smaller details that truly captured my attention. The weathered inscriptions on the rock faces, the hidden niches housing small deities, the intricate carvings on pillars and doorways – these are the whispers of history, the stories that aren't found in textbooks. The experience of photographing the Rockfort was more than just documenting a historical site; it was a conversation with the past. The rock itself seemed to emanate a sense of timeless presence, a silent witness to the ebb and flow of human ambition and devotion. As I descended, leaving the towering rock behind, I carried with me not just images, but a profound sense of connection to a place where history, spirituality, and human ingenuity converge. The Rockfort is not just a fort; it is a living monument, a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit.

Sri Siva Vishnu Temple Lanham

Sri Siva Vishnu Temple in Lanham, Maryland, dedicated to Siva, Vishnu, and a constellation of regional deities, opens at 6:00 AM and keeps rituals running through 9:00 PM, sequencing morning suprabhatam, daily homams, and evening sahasranama archanas across two granite shrines linked by a shared mandapam ([1][2]). Volunteer desk captains manage parking lots, shoe rooms, and darshan queues via digital displays so weekday devotees and weekend tour groups flow smoothly between the Saiva and Vaishnava sanctums ([1][3]). Security teams coordinate with Prince George’s County police during festival surges, monitor CCTV networks, and audit life-safety systems that include sprinklers, smoke detection, and backup power tested monthly ([3][5]). Elevators, ramps, tactile paving, and loaner wheelchairs maintain circulation between the sanctum, canteen, and cultural hall; ushers offer assistive listening headsets and bilingual signage for Tamil, Telugu, and English programming ([1][4]). Custodians follow two-hour cleaning cycles covering granite floors, brass thresholds, and ablution stations, while mechanical crews schedule filter changes and insulation checks ahead of humid Chesapeake summers ([3][5]). Community kitchens operate under separate HVAC zoning and grease recovery, keeping prasad production compliant with Maryland health codes. Preventive maintenance dashboards log priest schedules, chillers, fire systems, and accessibility inspections; 2025 county reviews recorded zero violations, confirming the temple remains fully operational and compliant for daily worship, cultural classes, and large-format festivals ([3][4][5]).

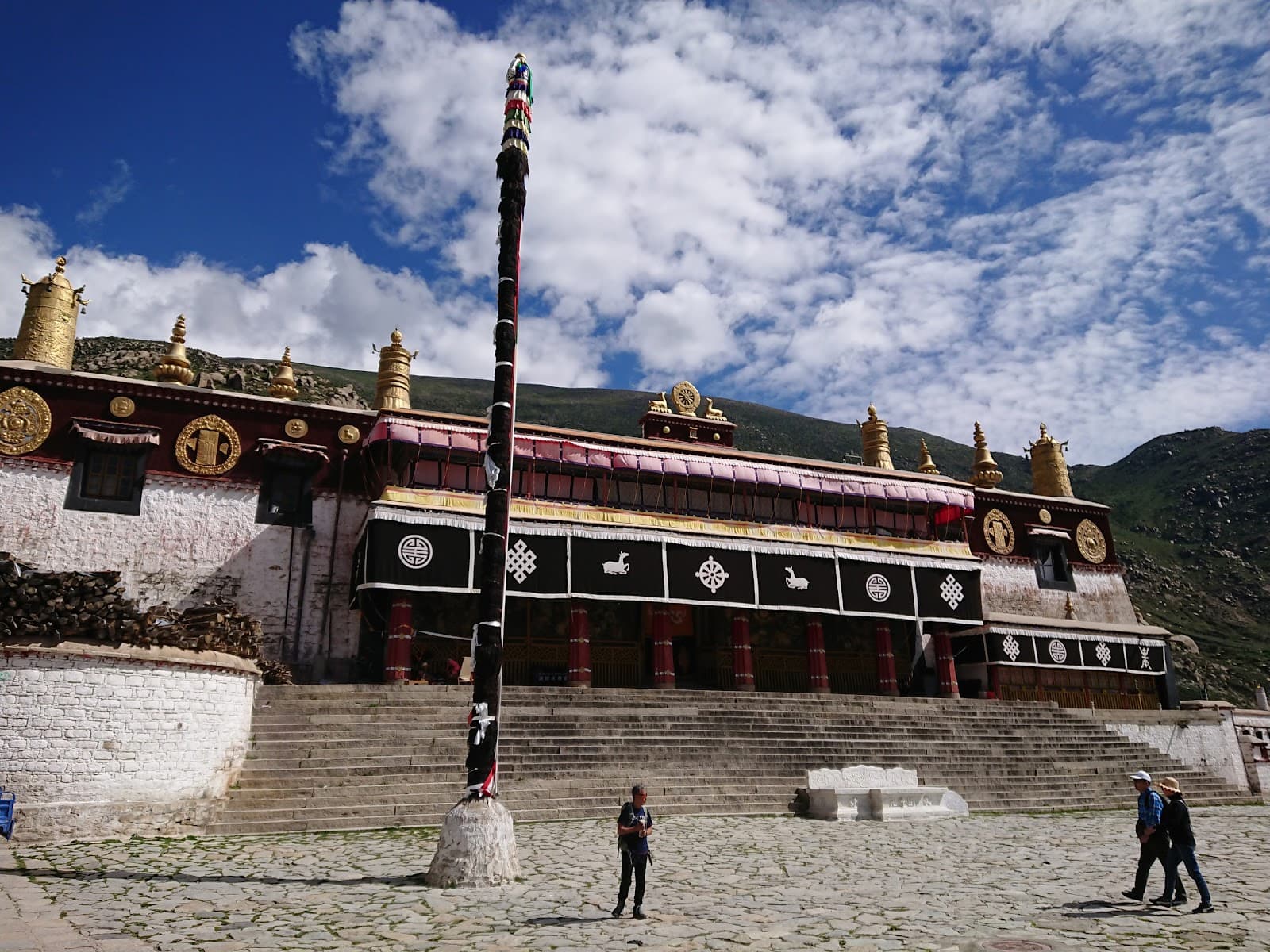

Drepung Monastery Lhasa Tibet

Drepung Monastery, located in Lhasa, Tibet, represents one of the three great Gelugpa monasteries in Tibet and stands as a major center for Tibetan Buddhist learning, constructed in the 15th century CE by Jamyang Chojey, a disciple of Tsongkhapa who established the Gelugpa school with strong connections to Indian Buddhist scholastic traditions, demonstrating the profound transmission of Indian Buddhist philosophy and learning traditions to Tibet, which has maintained deep cultural, religious, and historical connections with India for over two millennia. The monastery complex, constructed primarily from stone, wood, and earth with extensive decorative elements, features a massive structure containing numerous temples, chapels, assembly halls, debate courtyards, and residential quarters arranged according to Indian Buddhist monastery planning principles, with the overall design reflecting mandala-based cosmological principles found in Indian Buddhist architecture. The monastery’s architectural design demonstrates direct influence from Indian Buddhist monastery architecture, particularly the Nalanda model, with the overall plan, debate courtyards, and learning facilities reflecting traditions that were transmitted to Tibet through centuries of cultural exchange, while the emphasis on Indian Buddhist scholastic traditions demonstrates the transmission of Indian Buddhist philosophy to Tibet. Archaeological and historical evidence indicates the monastery was constructed with knowledge of Indian Buddhist scholastic traditions and architectural treatises, reflecting the close cultural connections between Tibet and India during the medieval period, when Indian Buddhist scholars, texts, and philosophical traditions continued to influence Tibetan Buddhism. The monastery has served as a major center for Tibetan Buddhist learning and practice for over five centuries, maintaining strong connections to Indian Buddhist traditions through the study of Indian Buddhist texts, philosophy, and debate traditions. The monastery has undergone multiple expansions and renovations over the centuries, with significant additions conducted to accommodate growing numbers of monks and expanding educational programs. Today, Drepung Monastery continues to serve as an important place of Buddhist worship and learning in Tibet, demonstrating the enduring influence of Indian Buddhist scholastic traditions on Tibetan culture and serving as a powerful symbol of Tibet’s deep connections to Indian civilization through the study and practice of Indian Buddhist philosophy. ([1][2])

Shawala Teja Singh Temple Sialkot Punjab

The Shawala Teja Singh Temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, stands as a profound testament to India's millennia-spanning spiritual and architectural heritage in Sialkot, Punjab Province, Pakistan [3]. This sacred edifice, rooted in the continuous tradition of Indian civilization, embodies indigenous architectural styles, materials, and cultural practices that reflect the deep historical roots of the subcontinent [1] [5]. Constructed primarily in the Nagara architectural style, with influences from regional Punjabi and Indo-Islamic aesthetics, the temple showcases a layered history of design and craftsmanship [1]. While specific dimensions are not widely documented, the temple's structure typically features a curvilinear shikhara (spire) characteristic of North Indian temple architecture, rising above the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) [3]. The construction predominantly utilizes local brick and lime mortar, materials historically prevalent in the region, with later additions potentially incorporating stucco and plasterwork [2]. The temple's exterior and interior once featured intricate carvings, sculptures, and vibrant murals, though many of these decorative elements have suffered degradation over time [1]. Historical accounts mention beautiful marble floors and ornate pillars, indicative of the refined craftsmanship employed during its construction and subsequent embellishments [1]. The spatial arrangement follows the traditional Hindu temple plan, with a central shrine housing the deity, surrounded by circumambulatory paths (pradakshina-patha) [3]. While advanced technical specifications like water management systems or defensive features are not explicitly detailed in available records, the temple's elevated position on a dune along Allama Iqbal Road suggests a deliberate choice for prominence and perhaps natural protection . Currently, the Shawala Teja Singh Temple is recognized as a protected heritage site, undergoing significant conservation and restoration efforts [2] [3]. The Pakistan government, through the Evacuee Trust Property Board (ETPB), has undertaken renovation work to restore the temple to its original design, including whitewashing the entire building, fixing the main entrance, and constructing boundary walls for security [2]. Archaeological findings are not extensively reported, but the ongoing restoration work provides opportunities for deeper understanding of its construction phases and earlier forms [2]. The temple is now formally handed over to the Pakistan Hindu Council, facilitating pilgrim visits and religious rituals, thereby ensuring its active programming and continued spiritual significance for the local Hindu community [2] [3]. Accessibility has been improved, and the site is maintained to allow visitor flow, symbolizing the enduring legacy of Indian cultural traditions [2]. The operational readiness of the temple underscores its role as a living heritage site, continuously serving its original purpose while standing as a monument to India's profound and unbroken cultural continuum [2].

Amber Fort Jaipur

The ochre walls of Amber Fort, constructed during the reign of Raja Man Singh I in the 16th century (1550 CE), evoke the splendor of Rajasthan ([1][2]). This fort represents a compelling fusion of Mughal and Rajput military architectural traditions ([3]). Upon entry through the Suraj Pol (Sun Gate), one immediately perceives the layered construction, reflecting the contributions of successive Rajput rulers ([4]). Intricate carvings embellishing the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audience) depict elephants and floral motifs, demonstrating a harmonious blend of strength and aesthetic grace ([5]). Moving inward, the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) showcases lavish ornamentation, including mosaics crafted from glass and precious stones ([2]). Famously, the Sheesh Mahal (Mirror Palace) illuminates with minimal light, a remarkable feat of design ingenuity ([3]). Granite and sandstone blocks, meticulously carved, constitute the primary building materials ([1]). Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, likely influenced the fort's layout, creating harmony and balance, though specific textual references are currently unavailable ([4]). From the zenana (women's quarters), the panoramic vista of Maota Lake provides a serene counterpoint to the fort's imposing structure ([5]). The fort stands as a powerful reminder of Rajasthan's rich history and cultural legacy ([1][2]). The use of red sandstone, marble, white marble, lacquer, and mortar further accentuates the fort's grandeur ([6]). The fort's architecture includes elements of Hindu and Islamic design, reflecting the cultural exchange of the period ([3]). Amber Fort is a testament to the architectural prowess and artistic vision of the Rajput Maharajas ([1][2]).

Shri Lakshmi Narayan Mandir Karachi

Shri Lakshmi Narayan Mandir, located in Karachi’s Saddar area along the banks of the historic Indus River, represents a significant 19th-century Hindu temple complex dedicated to Lakshmi and Narayan (Vishnu), serving as a testament to the continuity of Vaishnava worship traditions in the Sindh region that was historically part of the greater Hindu rashtra extending across the Indian subcontinent. The temple, constructed during the British colonial period when Hindu communities in Sindh were flourishing and maintaining strong connections to their religious and cultural heritage, features distinctive architecture that blends traditional North Indian temple design with local Sindhi adaptations, reflecting the synthesis of pan-Indian Hindu traditions with regional cultural practices. The temple complex, originally more extensive but now reduced due to urban development, features a main sanctum housing images of Lakshmi and Narayan, surrounded by subsidiary shrines and a courtyard that has served as a center of Hindu worship in Karachi for over a century. The site’s location along the Indus River, one of the cradles of ancient Indian civilization, reflects the deep historical connections between Hindu religious practices and the river systems that sustained ancient Indian kingdoms. The temple serves as an important center for Vaishnava worship, particularly during festivals associated with Lakshmi and Vishnu, demonstrating the continuity of Vedic and Puranic Hindu traditions in Pakistan. Archaeological and historical evidence indicates the temple has undergone multiple renovations, with the current structure dating primarily to the 19th century but incorporating elements that reflect centuries of Hindu architectural evolution in the region. Today, Shri Lakshmi Narayan Mandir stands as a symbol of the Vaishnava Hindu heritage of Sindh and the region’s historical connection to the greater Hindu rashtra, serving as a reminder of the sophisticated religious and cultural traditions that flourished in regions that were integral parts of ancient Indian civilization. ([1][2])

Shiva Temple Bur Dubai / Jebel Ali

Dubai’s Shiva Temple, founded in 1958 beside the Creek in Bur Dubai, served generations of labourers and merchants in a 250-square-metre upstairs hall until 2024, when the lingam and utsava idols were ceremoniously relocated to the new Jebel Ali Hindu Temple to ease crowding and comply with safety requirements ([1][2]). In its historic Al Fahidi setting the shrine shared a courtyard with Krishna Mandir and Gurudwara, with thousands lining the narrow stair for Maha Shivaratri jalabhisheka. The new Jebel Ali sanctum—opened January 2024 ahead of Maha Shivaratri—retains the same lingam and panchloha icons, now set within a larger abhishekam chamber clad in black granite, equipped with dedicated jalabhisheka drains, overhead kalasa water lines, and 360° darshan space for 500 devotees at a time. Rituals run from 5:30 AM Rudra Abhishekam to midnight vigil on Mondays, with daily arti at 7:00 AM/1:00 PM/8:00 PM, periodic Pradosham ceremonies, and Sani Pradosham homa in an adjoining yajna shala. Devotees pre-book milk offerings via QR codes, deposit coconuts at stainless-steel counters, and collect prasad from volunteers. The temple’s management preserves Bur Dubai heritage by maintaining a memorial alcove with photographs, the original teak arti lamp, and oral history kiosks documenting six decades beside the Creek.

Mysore Palace Mysuru

The Mysore Palace, or Amba Vilas Palace, isn't merely a structure; it's a statement. A statement of opulence, a testament to craftsmanship, and a living chronicle of a dynasty. As a Chennai native steeped in the Dravidian architectural idiom of South Indian temples, I found myself both captivated and challenged by the Indo-Saracenic style that defines this majestic palace. The blend of Hindu, Muslim, Rajput, and Gothic elements creates a unique architectural vocabulary, a departure from the gopurams and mandapas I'm accustomed to, yet equally mesmerizing. My first impression was one of sheer scale. The sprawling palace grounds, meticulously manicured, prepare you for the grandeur within. The three-storied stone structure, with its grey granite base and deep pink marble domes, stands as a beacon against the Mysore sky. The central arch, adorned with intricate carvings and flanked by imposing towers, draws the eye upwards, culminating in the breathtaking five-story gopuram. This fusion, the gopuram atop an Indo-Saracenic structure, is a powerful symbol of the cultural confluence that shaped Mysore's history. Stepping inside, I was immediately transported to a world of intricate detail. The Durbar Hall, with its ornate pillars, stained-glass ceilings, and intricately carved doorways, is a spectacle of craftsmanship. The pillars, far from being uniform, display a fascinating variety of designs, each a testament to the skill of the artisans. I noticed subtle variations in the floral motifs, the scrollwork, and even the miniature sculptures adorning the capitals. This attention to detail, reminiscent of the meticulous carvings found in Chola temples, spoke volumes about the dedication poured into this palace. The Kalyanamantapa, the marriage hall, is another jewel in the palace's crown. The octagonal hall, with its vibrant stained-glass ceiling depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, is a riot of color and light. The floor, paved with exquisite mosaic tiles, adds another layer of intricacy. While the overall style is distinctly different from the mandapas found in South Indian temples, I could appreciate the shared emphasis on creating a sacred, visually stunning space. Exploring further, I was particularly drawn to the Gombe Thotti, or Doll's Pavilion. This museum houses a remarkable collection of dolls from around the world, offering a glimpse into diverse cultures and artistic traditions. While not strictly architectural, it provided a fascinating cultural context for the palace and its inhabitants. The palace's exterior, particularly during the evening illumination, is truly magical. Thousands of bulbs outline the structure, transforming it into a shimmering spectacle. This, I felt, was a modern interpretation of the kuthuvilakku, the traditional oil lamps used to illuminate temple towers during festivals. While the technology is different, the effect is the same – a breathtaking display of light and shadow that enhances the architectural beauty. One aspect that particularly resonated with my background in South Indian temple architecture was the use of open courtyards. These courtyards, while smaller than the prakarams found in temples, serve a similar purpose – providing ventilation, natural light, and a sense of tranquility amidst the grandeur. They also offer framed views of different parts of the palace, creating a dynamic visual experience as one moves through the complex. The Mysore Palace is not just a palace; it's a living museum, a testament to the artistry and vision of its creators. It's a place where architectural styles converge, where history whispers from every corner, and where the grandeur of the past continues to captivate visitors from around the world. As I left the palace grounds, I carried with me not just images of its splendor, but a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of Indian architecture and the unique stories it tells.

Banteay Samre Siem Reap Cambodia

Located 12 kilometers east of Angkor, Banteay Samre exemplifies Khmer Vaishnavite temple architecture dating back to the 12th century CE, during the reign of Suryavarman II ([1][2]). Dedicated to Vishnu, the temple illustrates the transmission of Indian Vaishnavite traditions to Cambodia during the Angkorian period ([1][2]). Its layout, featuring a central sanctuary with enclosures and galleries, reflects Indian Vaishnavite temple planning principles, similar to complexes found in India ([1][2]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls depict scenes from Vaishnavite mythology, including Vishnu's avatars and narratives from the Ramayana and Mahabharata ([1][2]). These carvings demonstrate the sophisticated understanding of Indian iconography by Khmer artists ([1][2]). During the medieval period, temple architecture incorporated the concept of Mount Meru in its central tower, surrounded by galleries, aligning with Indian Vaishnavite planning principles ([1][2]). The central tower, or Shikhara (Spire), rises majestically, embodying the cosmic mountain ([1][2]). Sandstone blocks, meticulously fitted together without mortar, showcase engineering techniques potentially transmitted from India to Cambodia ([1][2]). Lime mortar was used as an adhesive in certain areas, further securing the structure ([3]). Archaeological excavations have uncovered the temple's role as a center for Vishnu worship, with inscriptions providing evidence of the transmission of Indian Vaishnavite texts and practices ([1][2][3]). The Garbhagriha (Sanctum) likely housed an idol of Vishnu, the supreme deity in Vaishnavism ([3]). Now a part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Banteay Samre attests to the impact of Indian culture and architecture on Southeast Asia ([4][5]). Ongoing research and conservation efforts aim to protect this cultural treasure, demonstrating Indian civilization's influence on Southeast Asian religious and artistic traditions ([4][5]). The temple's Mandapa (Pillared Hall) would have served as a space for devotees to gather and offer prayers ([5]). The use of laterite in the foundation provided a stable base for the sandstone superstructure ([3]).

Shiv-Parvati Mandir Hnahthial

The air hung thick and humid, a stark contrast to the arid landscapes of Rajasthan I’m accustomed to. Here in Hnahthial, Mizoram, nestled amidst verdant hills, the Shiv-Parvati Mandir stands as a testament to the surprising religious diversity of this northeastern state. The temple, a relatively recent construction compared to the ancient forts and palaces I’ve explored back home, possesses a unique charm, blending traditional North Indian temple architecture with local Mizo influences. The first thing that struck me was the vibrant colours. Unlike the sandstone hues of Rajasthan’s temples, this one is painted in bright shades of orange, yellow, and red, creating a cheerful, almost festive atmosphere. The main structure rises in a series of tiered roofs, reminiscent of a classic Nagara style shikhara, yet the curvature is gentler, less pronounced. Instead of intricate carvings, the exterior walls are adorned with simpler, bolder motifs – geometric patterns and stylized floral designs that hint at Mizo artistic traditions. Ascending the steps to the main entrance, I noticed the absence of the elaborate gateways and towering gopurams common in South Indian temples. The entrance is relatively modest, framed by two pillars decorated with colourful depictions of deities. Stepping inside, I was greeted by the cool, dimly lit interior. The main sanctum houses the idols of Shiva and Parvati, adorned with vibrant clothing and garlands. The atmosphere was serene, filled with the murmur of prayers and the scent of incense. What truly captivated me was the seamless integration of local elements within the predominantly North Indian architectural framework. The use of locally sourced materials, like bamboo and wood, in the construction of the ancillary structures surrounding the main temple, is a clear example. I observed a small pavilion, crafted entirely from bamboo, serving as a resting place for devotees. The intricate weaving patterns on the bamboo walls showcased the remarkable craftsmanship of the local artisans. The temple complex also houses a small garden, a welcome splash of green amidst the concrete structures. Unlike the meticulously manicured gardens of Rajasthan’s palaces, this one felt more natural, with flowering plants and fruit trees growing in abundance. The gentle rustling of leaves in the breeze added to the tranquil atmosphere. Interacting with the local priest, I learned about the history of the temple. It was fascinating to hear how the local community, predominantly Christian, embraced the construction of this Hindu temple, reflecting the spirit of religious tolerance that permeates Mizoram. He explained how the temple serves as a focal point not just for religious ceremonies but also for social gatherings and cultural events, further strengthening the bonds within the community. As I walked around the temple complex, observing the devotees offering prayers, I couldn't help but draw parallels between the religious practices here and those back home. Despite the geographical distance and cultural differences, the underlying devotion and reverence remained the same. The ringing of bells, the chanting of mantras, the offering of flowers – these rituals transcended regional boundaries, reminding me of the unifying power of faith. Leaving the Shiv-Parvati Mandir, I carried with me a sense of quiet admiration. This temple, a unique blend of architectural styles and cultural influences, stands as a symbol of harmony and acceptance. It’s a testament to the fact that even in the most unexpected corners of India, one can find expressions of faith that resonate deeply with the human spirit. It’s a far cry from the majestic forts and palaces of Rajasthan, yet it holds its own unique charm, offering a glimpse into the rich tapestry of India’s cultural and religious landscape.

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides