Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

Ita Fort Itanagar

The midday sun cast long shadows across the undulating hills surrounding Itanagar, highlighting the weathered brick-red ramparts of the Ita Fort. Ascending the gentle slope towards the main entrance, I felt a palpable shift in atmosphere, a sense of stepping back in time. This wasn't merely a historical site; it was a living testament to the architectural ingenuity of the Tai-Ahom people who once ruled this region. Ita Fort, also known as the Ita Krung, isn't a fort in the conventional sense of a singular fortified structure. It's more accurately described as a fortified complex, a sprawling network of ramparts, gateways, and earthen mounds enclosing a vast area. The walls, constructed primarily of bricks, are remarkable for their sheer size and the irregular, almost organic way they follow the contours of the land. Unlike the precisely measured and geometric fortifications of the Mughals, Ita Fort displays a different kind of sophistication – an understanding of the landscape and its defensive potential. Passing through the main gateway, a modest arched opening in the thick walls, I found myself in a large open space. Here, the remnants of several structures were visible – low brick platforms, scattered fragments of walls, and the intriguing circular depressions that are believed to have been the bases of granaries. The absence of elaborate ornamentation or intricate carvings was striking. The beauty of Ita Fort lies in its stark simplicity, its functional design, and the sheer scale of the undertaking. The bricks themselves are a story. Large and uneven, they bear the marks of hand-crafting, a tangible connection to the builders who labored centuries ago. The mortar, a mixture of clay and organic materials, has weathered over time, giving the walls a textured, almost tapestry-like appearance. I ran my hand over the rough surface, imagining the hands that had placed these very bricks, the generations who had sought shelter within these walls. Climbing to the highest point of the ramparts, I was rewarded with a panoramic view of the surrounding hills and the valley below. It was easy to see why this location was chosen for the fort. The elevated position provided a clear line of sight for miles, allowing the inhabitants to monitor the approaches and defend against potential invaders. The strategic importance of Ita Fort was undeniable. One of the most fascinating aspects of Ita Fort is the mystery surrounding its precise history. While it is generally attributed to the Tai-Ahom kingdom, the exact date of construction and the details of its use remain shrouded in some ambiguity. Local legends and oral traditions offer glimpses into the fort's past, but concrete archaeological evidence is still being unearthed. This air of mystery adds another layer to the experience, a sense of engaging with a puzzle whose pieces are slowly being revealed. As I descended from the ramparts, the late afternoon sun cast a golden glow over the ancient bricks. Ita Fort is more than just a collection of ruins; it's a portal to a vanished era, a reminder of the rich and complex history of this region. It's a place where the whispers of the past mingle with the sounds of the present, offering a unique and deeply rewarding experience for anyone willing to listen. It’s a site that deserves greater attention, not just for its architectural significance but also for the stories it holds within its weathered walls. My visit left me with a profound sense of awe and a renewed appreciation for the ingenuity and resilience of those who came before us.

Shamlaji Temple Shamlaji

The crisp Gujarat air, scented with incense and marigold, welcomed me as I approached the Shamlaji temple. Nestled amidst the Aravalli hills, near the banks of the Meshwo river, this ancient shrine dedicated to Lord Vishnu, or more specifically, his Krishna avatar, felt instantly different from the cave temples of Maharashtra I'm so accustomed to. Here, sandstone replaces basalt, and the intricate carvings speak a different dialect of devotion. The temple complex, enclosed within a high fortified wall, immediately conveyed a sense of history and sanctity. Unlike the rock-cut architecture of my home state, Shamlaji showcases a stunning example of Maru-Gurjara architecture. The shikhara, the towering structure above the sanctum, is a masterpiece of intricate carvings. Its layered, ascending form, adorned with miniature shrines and celestial figures, draws the eye heavenward. I spent a good hour simply circling the temple, absorbing the sheer detail. Every inch seemed to narrate a story – episodes from the epics, celestial musicians, and intricate floral motifs, all carved with an astonishing precision. Stepping inside the main mandapa, or hall, I was struck by the play of light and shadow. The intricately carved pillars, each unique in its design, created a mesmerizing pattern as sunlight filtered through the jaalis, or perforated stone screens. The air was thick with the murmur of prayers and the scent of sandalwood. Devotees offered flowers and whispered their devotions to the deity, their faces illuminated by the flickering lamps. It was a scene that resonated with a deep sense of spirituality, a palpable connection to centuries of worship. The garbhagriha, the inner sanctum, houses the main deity, Shamlaji, a form of Krishna. While photography isn't permitted inside, the mental image I carry is vivid. The deity, bathed in the soft glow of oil lamps, exuded an aura of tranquility and power. The reverence of the devotees, the chanting of mantras, and the fragrance of incense created an atmosphere charged with devotion. What truly captivated me at Shamlaji was the confluence of influences. While the core architectural style is Maru-Gurjara, I noticed subtle hints of influences from other regions. Some of the sculptural elements reminded me of the Hoysala temples of Karnataka, while certain decorative motifs echoed the art of the Solankis of Gujarat. This fusion of styles speaks volumes about the historical and cultural exchanges that have shaped this region. Beyond the main temple, the complex houses several smaller shrines dedicated to other deities. I explored these with equal fascination, noting the variations in architectural style and the unique stories associated with each shrine. One particularly intriguing shrine was dedicated to Devi, the consort of Vishnu. The carvings here were more dynamic, depicting the goddess in her various forms, from the gentle Parvati to the fierce Durga. My exploration extended beyond the temple walls. The surrounding landscape, with its rolling hills and the meandering Meshwo river, added another layer to the experience. I learned that the river is considered sacred, and pilgrims often take a dip in its waters before entering the temple. This connection between the natural environment and the spiritual realm is something I’ve often observed in sacred sites across India, and it always resonates deeply with me. Leaving Shamlaji, I carried with me not just photographs and memories, but a deeper understanding of the rich tapestry of Indian art and spirituality. This temple, with its stunning architecture, its palpable sense of devotion, and its unique blend of cultural influences, stands as a testament to the enduring power of faith and the artistic brilliance of our ancestors. It’s a place I would urge anyone exploring the heritage of Western India to experience firsthand. It's a world away from the caves of Maharashtra, yet equally captivating, a testament to the diverse beauty of our nation's sacred spaces.

Srikalahasti Temple Srikalahasti

The air hung thick with incense and the murmur of chanting as I stepped through the towering gopuram of the Srikalahasti Temple. Sunlight, fractured by the intricate carvings, dappled the stone floor, creating an ethereal atmosphere. This wasn't just another temple on my UNESCO World Heritage journey across India; Srikalahasti held a different energy, a palpable sense of ancient power. Located in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, this temple, dedicated to Vayu, the wind god, is a testament to centuries of devotion and architectural brilliance. My eyes were immediately drawn upwards to the main Vimana, the Shikharam, soaring above the inner sanctum. This impressive structure, known as the Vayu Lingam, is not a sculpted idol but a natural rock formation believed to be a manifestation of Vayu. The flickering lamps surrounding it cast dancing shadows, adding to the mystique. The temple's Dravidian architecture is a marvel, with its intricate carvings depicting scenes from Hindu mythology. I spent a considerable amount of time studying the detailed friezes, each panel narrating a story, a testament to the skill of the artisans who crafted them centuries ago. The vibrant colours, though faded with time, still hinted at the temple's former glory. One of the most striking features of Srikalahasti is its massive, 100-pillar mandapam. The sheer scale of this hall is breathtaking. Each pillar is a work of art, adorned with elaborate carvings of deities, mythical creatures, and floral motifs. I could almost hear the echoes of ancient ceremonies and festivals that must have taken place within these hallowed walls. Walking through the mandapam, I felt a sense of connection to the generations of devotees who had walked this same path before me. The temple complex is vast, encompassing several smaller shrines dedicated to various deities. I explored each one, noting the unique architectural nuances and the distinct atmosphere they held. The shrine of Kalahasteeswara, a form of Shiva, is particularly noteworthy. The legend of the spider, the snake, and the elephant, each offering their devotion to Shiva in their own way, is deeply embedded in the temple's lore and adds another layer of spiritual significance to the site. Beyond the architectural grandeur, what truly captivated me at Srikalahasti was the palpable devotion of the pilgrims. From the elderly woman whispering prayers with closed eyes to the young family offering coconuts, the air was thick with faith. Witnessing this fervent devotion firsthand gave me a deeper understanding of the temple's significance, not just as a historical monument but as a living, breathing centre of spirituality. As I left the temple, the chanting still resonated in my ears. Srikalahasti is more than just a collection of stones and carvings; it's a testament to the enduring power of faith and the artistic brilliance of a bygone era. It's a place where history, mythology, and spirituality intertwine, creating an experience that stays with you long after you've left its sacred grounds. Of all the UNESCO sites I've visited in India, Srikalahasti holds a special place, a reminder of the rich tapestry of culture and belief that makes this country so unique. The wind, whispering through the temple towers, seemed to carry the echoes of centuries of prayers, a testament to the enduring spirit of this ancient sanctuary.

Gomateshwara Statue Shravanabelagola

The midday sun beat down on my neck, a stark contrast to the cool, shaded groves I’d grown accustomed to in the Himalayas. Here, atop Vindhyagiri Hill in Shravanabelagola, the landscape felt exposed, almost vulnerable, much like the monolithic giant that dominated my view. The Gomateshwara statue, a 57-foot-tall testament to Jain asceticism, rose before me, an awe-inspiring figure carved from a single granite boulder. Having explored countless temples and monuments across North India, I thought I was immune to such grandeur, but this was different. This wasn't just a statue; it was a palpable presence. The climb itself had been a pilgrimage of sorts. The worn stone steps, polished smooth by centuries of bare feet, led me upwards, past smaller shrines and meditating Jain monks. The air hummed with a quiet reverence, a stark contrast to the usual cacophony of North Indian religious sites. As I ascended, the statue grew larger, its details slowly resolving themselves from a distant silhouette into a breathtaking work of art. Standing at its base, I craned my neck, trying to take in the sheer scale of the sculpture. Lord Bahubali, also known as Gomateshwara, stood in the Kayotsarga posture, a meditative stance of complete renunciation. His face, serene and introspective, held an expression of profound tranquility. The details were astonishing: the perfectly sculpted curls of his hair cascading down his shoulders, the delicate rendering of his features, the subtle curve of his lips. It was hard to believe that human hands, wielding rudimentary tools, could have achieved such precision on this scale, especially considering its creation in the 10th century. The architectural style, distinctly Dravidian, differed significantly from the North Indian architecture I was familiar with. There were no elaborate carvings or ornate decorations. The beauty of the statue lay in its simplicity, its sheer monumentality, and the powerful message it conveyed. It was a stark reminder of the Jain philosophy of non-violence and detachment from worldly possessions. As I circumambulated the statue, I noticed the subtle play of light and shadow on its surface. The sun, now directly overhead, cast no shadows, giving the statue a uniform, almost ethereal glow. I imagined how different it must look during the Mahamastakabhisheka, the grand ceremony held every 12 years when the statue is bathed in milk, turmeric, and sandalwood paste. Witnessing that spectacle must be an experience unlike any other. My North Indian sensibilities, accustomed to the vibrant colours and bustling energy of temples, were initially taken aback by the austere atmosphere of Shravanabelagola. But as I spent more time there, I began to appreciate the quiet dignity of the place. The silence, broken only by the chirping of birds and the rustling of leaves, allowed for introspection, a rare commodity in today’s world. Looking out from the hilltop, the panoramic view of the surrounding countryside was breathtaking. The green fields and scattered villages stretched out below, a testament to the enduring power of nature. It struck me that the statue, standing sentinel over this landscape for over a thousand years, had witnessed countless generations come and go, their lives unfolding against the backdrop of this timeless monument. Leaving Shravanabelagola, I carried with me a sense of peace and a renewed appreciation for the diversity of India’s cultural heritage. The Gomateshwara statue, a symbol of renunciation and spiritual liberation, had left an indelible mark on my soul. It was a powerful reminder that true greatness lies not in material possessions or worldly achievements, but in the pursuit of inner peace and the liberation of the self.

Krishna Temple Bur Dubai

The Krishna Temple in Bur Dubai has been Dubai’s oldest continuously operating Hindu shrine since 1958, tucked on the mezzanine of a sandalwood-scented souq courtyard in the historic Al Fahidi district where hundreds climb a narrow stair each dawn for darshan of Sri Nathji, Radha-Krishna, Mahalakshmi, and Sai Baba before winding through the lattice-screen corridor that overlooks the Creek ([1][2]). The 1,500-square-foot mandir retains teak balustrades, hand-carved pillars, brass finials, and the nine-domed roofline that peeks above coral-stone shophouses; priests weave through the throng performing arti with oil lamps held inches from glass-fronted sancta while volunteers chant bhajans. Daily timings stretch 5:00 AM-11:30 AM and 5:00 PM-9:30 PM, accommodating 3,000 devotees on weekdays and up to 6,000 during Janmashtami or Diwali. The temple’s shoe racks, prasad counter, and queue rails occupy the ground-level courtyard shared with souvenir shops and the adjacent Sikh Gurudwara, symbolising Dubai’s intercultural tapestry. Canonical rituals include Radha Ashtami, Satyanarayana katha, Tulsi Vivah, and mass annadhanam delivered by Indian restaurants who donate vegetarian meals. The small admin office manages marriage registrations, birth certificate attestations, and diaspora documentation in coordination with the Indian Consulate ([2][3]).

Gnana Saraswathi Temple Basar Telangana

The melodic chanting of Vedic hymns hung heavy in the air, a palpable presence that wrapped around me as I stepped into the courtyard of the Gnana Saraswathi Temple in Basar. Having explored countless temples across North India, I’d arrived with a seasoned eye, ready to dissect and appreciate the nuances of this southern shrine dedicated to the goddess of knowledge. The energy here, however, was distinctly different, a vibrant hum that resonated with the scholarly pursuits it championed. Located on the banks of the Godavari River, the temple complex felt ancient, its stones whispering tales of centuries past. Unlike the towering, ornate structures I was accustomed to in the north, the architecture here was more subdued, yet no less compelling. The main temple, dedicated to Goddess Saraswathi, is relatively small, its entrance guarded by a modest gopuram. The simplicity, however, belied the temple's significance. Inside, the deity, adorned in vibrant silks and glittering jewels, held a captivating presence. She wasn't depicted as the fierce, warrior goddess often seen in North India, but rather as a serene embodiment of wisdom and learning, a subtle yet powerful distinction. Adjacent to the Saraswathi temple stands a shrine dedicated to Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and a little further, one for Kali, the goddess of power. This trinity, housed within the same complex, spoke volumes about the interconnectedness of knowledge, prosperity, and strength, a philosophy deeply embedded in Indian thought. What truly set the Gnana Saraswathi Temple apart was the palpable emphasis on education. The temple is believed to be one of the three places where the Goddess Saraswathi manifested herself, the other two being Kashmir and Sringeri. This association with learning was evident everywhere. Students from across the region flocked to the temple, seeking blessings before exams. I witnessed families performing Aksharabhyasam, a sacred ceremony where children are initiated into the world of letters. The air thrummed with the quiet murmur of prayers and the rustle of palm leaves, a testament to the temple's continuing role as a centre of learning. The surrounding landscape further enhanced the temple's tranquil atmosphere. The Godavari River, flowing serenely beside the temple, added a layer of serenity to the already peaceful environment. The surrounding hills, dotted with lush greenery, provided a picturesque backdrop. I spent some time by the riverbank, watching the pilgrims take a holy dip, their faces reflecting a quiet devotion. One of the most intriguing aspects of the temple was the presence of a large number of ancient manuscripts, preserved within the temple complex. While I couldn't access them directly, the very knowledge of their existence added another layer of historical significance to the site. It spoke of a time when this temple served not just as a place of worship, but also as a repository of knowledge, a beacon of learning in the region. As I prepared to leave, I noticed a group of young children diligently practicing calligraphy on slates, their brows furrowed in concentration. It was a poignant reminder of the temple's enduring legacy, its continued relevance in a world increasingly driven by technology. The Gnana Saraswathi Temple wasn't just a place of worship; it was a living testament to the power of knowledge, a sanctuary where the pursuit of wisdom was celebrated and nurtured. My journey through North India had exposed me to countless architectural marvels and spiritual havens, but the Gnana Saraswathi Temple, with its unique blend of serenity and scholarly pursuit, left an indelible mark, a quiet echo of ancient wisdom resonating within me.

Pinjore Fort Panchkula

The midday sun cast long shadows across the Mughal Gardens, highlighting the geometric precision that frames the Pinjore Fort. Stepping through the arched gateway, I felt a palpable shift, a transition from the bustling present of Panchkula to the serene whispers of the past. This wasn't just another fort; it was a carefully curated experience, a blend of military might and refined aesthetics. The fort itself, known locally as Yadavindra Gardens, isn't a towering behemoth like some of the Rajput strongholds I've documented in Madhya Pradesh. Instead, it presents a more intimate scale, a series of interconnected structures nestled within the embrace of the gardens. The seven-terraced Mughal Gardens, inspired by the legendary Shalimar Bagh, are integral to the fort's character. Fountains, once powered by an ingenious system of natural springs, now lie dormant, yet the intricate channels and symmetrical flowerbeds still evoke a sense of grandeur. My lens was immediately drawn to the Sheesh Mahal, the palace of mirrors. While smaller than its namesake in Jaipur, the delicate inlay work here possesses a unique charm. Tiny fragments of mirror, meticulously arranged in floral patterns, catch the light, creating a kaleidoscope of reflections. I spent hours capturing the interplay of light and shadow, trying to convey the sheer artistry involved in this intricate craft. The Rang Mahal, with its open courtyards and intricately carved balconies, offered another perspective. I imagined the vibrant life that once filled these spaces, the rustle of silk, the melodies of court musicians, the scent of exotic perfumes. Climbing the steps to the upper levels of the fort, I was rewarded with panoramic views of the gardens and the surrounding Shivalik foothills. The strategic location of the fort, guarding the passage into the hills, became immediately apparent. The ramparts, though not as imposing as those of Gwalior Fort, still spoke of a time of skirmishes and sieges. I noticed the remnants of defensive structures, the strategically placed bastions, the narrow embrasures for archers. These details, often overlooked by casual visitors, are crucial in understanding the fort's historical context. What struck me most about Pinjore was the seamless integration of nature and architecture. The gardens aren't merely an adjunct to the fort; they are an integral part of its design. The architects skillfully incorporated the natural contours of the land, using terraces and water channels to create a harmonious blend of built and natural environments. This sensitivity to the landscape is a hallmark of Mughal architecture, and it's beautifully exemplified here. As I wandered through the Jal Mahal, a pavilion situated amidst a tranquil water tank, I couldn't help but compare it to the water palaces of Mandu. While the scale and grandeur are different, the underlying principle of using water as a cooling and aesthetic element is the same. The reflections of the pavilion in the still water created a mesmerizing visual effect, a testament to the architects' understanding of light and perspective. My time at Pinjore Fort was a journey through layers of history, a testament to the enduring legacy of Mughal artistry and engineering. It's a place where the whispers of the past resonate in the present, inviting visitors to connect with a rich and complex heritage. As I packed my equipment, the setting sun cast a golden glow over the fort, etching the scene in my memory, a reminder of the beauty and resilience of India's architectural treasures. This wasn't just a photographic assignment; it was an immersive experience, a privilege to document a piece of history.

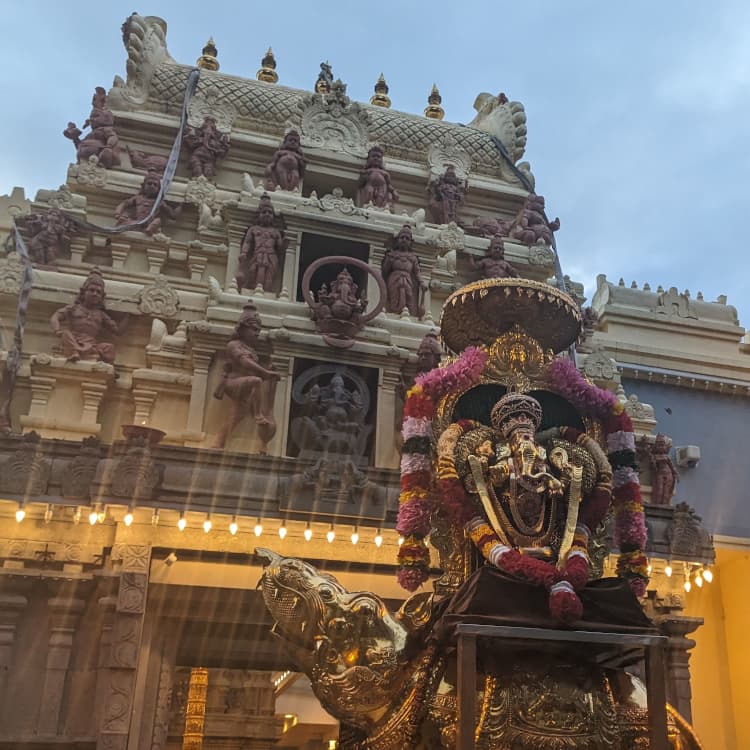

Sri Vakrathunda Vinayagar Temple The Basin

Sri Vakrathunda Vinayagar Temple The Basin is dedicated to Lord Ganesha and anchors The Basin, Victoria, on the foothills of the Dandenong Ranges ([1][2]). The hilltop mandir opens daily 6:00 AM-12:00 PM and 4:00 PM-8:30 PM, with Vinayagar Chathurthi and Thai Poosam schedules extending to 10:30 PM; marshals in high-visibility vests coordinate shuttle buses from the lower car park to keep the single-lane driveway clear ([1][4]). Mandapa floor markings separate pradakshina loops from queue lanes, and RFID counters at the entry tally pilgrim volumes so the volunteer command post can pace access into the sanctum ([1][5]). Annadhanam is served from a timber-lined dining hall with polished concrete floors, commercial dishwashers, and induction woks to reduce bushfire risk by avoiding naked flames ([1][3]). A 1:16 timber ramp with anti-slip mesh runs along the southern retaining wall, linking the car park to the mandapa, while stainless handrails, tactile paving, and hearing loop signage support inclusive access ([2]). Bushfire-ready shutters, ember screens, and a 90,000-litre tank plumbed to rooftop drenchers stand ready each summer, with CFA volunteers drilling annually alongside temple wardens ([2][5]). Wayfinding boards highlight refuge zones, first aid, and quiet meditation groves along the eucalyptus ridge, and QR codes push live updates about weather, kangaroo movement, and shuttle schedules directly to visitor phones ([1][6]). With emergency protocols rehearsed, food safety plans audited, and musician rosters published weeks ahead, the temple remains fully prepared for devotees, hikers, and school excursions seeking the hilltop shrine ([1][2]).

Neermahal Palace Melaghar Tripura

The shimmering reflection of Neermahal Palace rippled across Rudrasagar Lake, a sight that instantly justified the long journey to Melaghar, Tripura. The "Lake Palace," as it's often called, isn't the imposing sandstone behemoth one might expect from Rajasthan, but rather a unique blend of Hindu and Mughal architectural styles, a testament to Maharaja Bir Bikram Kishore Manikya Bahadur's vision in the early 20th century. Having documented over 500 monuments across India, I've become accustomed to the grandeur of empires past, but Neermahal held a distinct charm, a quiet dignity amidst the placid waters. The boat ride to the palace itself is an experience. The lake, vast and serene, creates a sense of anticipation, the palace gradually growing larger, its white and light pink facade becoming clearer against the backdrop of the green hills. As we approached, the intricate details began to emerge – the curved arches, the ornate domes, the delicate floral motifs. The blend of styles is striking. The domes and chhatris speak to the Mughal influence, while the overall structure, particularly the use of timber and the sloping roofs, leans towards traditional Hindu architecture. This fusion isn't jarring; it feels organic, a reflection of the cultural confluence that has shaped this region. Stepping onto the landing, I was immediately struck by the scale of the palace. It's larger than it appears from afar, spread across two courtyards. The western courtyard, designed for royal functions, is grand and open, while the eastern courtyard, the zenana, or women's quarters, is more intimate, with smaller rooms and balconies overlooking the lake. This segregation, typical of many Indian palaces, offers a glimpse into the social structures of the time. The interior, while sadly showing signs of neglect in places, still retains echoes of its former glory. The durbar hall, with its high ceilings and remnants of intricate plasterwork, speaks of lavish gatherings and royal pronouncements. The smaller rooms, once vibrant with life, now stand silent, their peeling paint and crumbling walls whispering stories of a bygone era. I spent hours exploring these spaces, my camera capturing the interplay of light and shadow, documenting the decay as much as the remaining beauty. One of the most captivating aspects of Neermahal is its setting. The lake isn't merely a backdrop; it's integral to the palace's identity. The reflection of the palace on the still water creates a mesmerizing visual, doubling its impact. The surrounding hills, covered in lush greenery, add another layer to the picturesque scene. I noticed several strategically placed balconies and viewing points, designed to maximize the views of the lake and surrounding landscape. It's clear that the Maharaja, a known connoisseur of beauty, intended for Neermahal to be a place of leisure and aesthetic appreciation. My visit to Neermahal wasn't just about documenting the architecture; it was about experiencing a place frozen in time. It was about imagining the lives lived within those walls, the laughter and music that once filled the courtyards, the boats gliding across the lake carrying royalty and guests. It was about witnessing the inevitable passage of time, the slow but relentless decay that affects even the grandest of structures. Neermahal, in its present state, is a poignant reminder of the impermanence of things, a beautiful ruin that continues to captivate and inspire. It's a place that deserves to be preserved, not just for its architectural significance, but for the stories it holds within its crumbling walls.

San Phra Kan Prang Khaek Lopburi

San Phra Kan, also known as Prang Khaek, located in Lopburi town, represents the oldest Khmer Hindu shrine in Central Thailand, dating to the 9th-10th centuries CE and constructed during the early Angkorian period, likely during the reign of Suryavarman II. The temple complex features three brick prangs (towers) arranged in a row, dedicated to the Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, demonstrating the syncretic nature of early Khmer religious practice. The complex spans approximately 0.5 hectares and features a rectangular laterite enclosure wall, though much has been lost to urban development. The three prangs, constructed primarily from brick with sandstone doorframes and decorative elements, rise to heights between 10 and 12 meters, with the central tower being slightly taller. The temple’s architectural style represents early Angkorian period, predating the more elaborate Baphuon and Angkor Wat styles, featuring simpler decorative elements and construction techniques. The complex includes evidence of stucco decoration, though most has been lost to weathering. Archaeological evidence indicates the temple served as an important early Khmer religious center in Central Thailand, establishing the foundation for later Khmer architectural developments in the region. The site has undergone restoration since the 1930s, involving structural stabilization and conservation. Today, San Phra Kan remains an important site for understanding early Khmer architecture in Thailand, attracting visitors interested in its historical significance as the oldest Angkorian temple in Central Thailand and its role in establishing Khmer cultural influence in the region. ([1][2])

Jageshwar Temples Almora

The crisp mountain air of Uttarakhand carried the scent of pine and something older, something sacred. I stood at the entrance to the Jageshwar temple complex, a sprawling tapestry of over 124 stone temples nestled within a deodar forest. It wasn't simply a collection of structures; it felt like stepping into a living, breathing organism that had evolved organically over centuries. The Jageshwar group isn't a planned, symmetrical layout like Khajuraho or Modhera; it's a cluster, a family of shrines that have grown around each other, whispering stories of devotion and architectural ingenuity. My initial impression was one of subdued grandeur. Unlike the towering, imposing structures of South India, these temples were more intimate, their grey stone surfaces softened by moss and lichen. The majority of the temples belong to the Nagara style of North Indian architecture, characterized by a curvilinear shikhara, the tower above the sanctum. However, the shikharas here possess a distinct local flavour. They are taller and more slender than those found in, say, Odisha, giving them an almost ethereal quality against the backdrop of the Himalayas. Several temples, particularly the larger ones dedicated to Jageshwar (Shiva) and Mrityunjaya, exhibit the classic tiered structure of the shikhara, with miniature replicas of the main tower adorning each level, diminishing in size as they ascend towards the finial. I spent hours wandering through the complex, tracing the weathered carvings on the doorways and pillars. The intricate detailing, though eroded by time and the elements, still spoke volumes of the skill of the artisans. Recurring motifs included stylized lotuses, geometric patterns, and depictions of divine figures – Shiva, Parvati, and Ganesha being the most prominent. One particular panel, on a smaller shrine dedicated to Nandi, caught my attention. It depicted a scene from Shiva's marriage to Parvati, the figures rendered with a surprising dynamism, their expressions almost palpable despite the wear and tear. The main Jageshwar temple, dedicated to the eponymous deity, is the largest and arguably the most impressive. Its towering shikhara dominates the skyline of the complex, drawing the eye upwards. Inside the sanctum, a lingam, the aniconic representation of Shiva, resides in a dimly lit chamber, imbued with a palpable sense of reverence. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of prayers, a testament to the fact that this is not merely an archaeological site but a living place of worship. What struck me most about Jageshwar was the sense of continuity. The architectural styles evident here span several centuries, from the early Gupta period to the later medieval era. You can trace the evolution of the Nagara style, observing the subtle changes in the shikhara design, the ornamentation, and the layout of the temples. This layering of history, this palpable connection to the past, is what sets Jageshwar apart. It's not a static museum piece; it's a dynamic testament to the enduring power of faith and the artistry of generations of builders. As the sun began to dip behind the mountains, casting long shadows across the complex, I felt a profound sense of peace. Jageshwar is more than just a collection of temples; it's a sanctuary, a place where the whispers of the past mingle with the prayers of the present. It's a place that reminds us of the enduring power of human creativity and the timeless search for the divine. And it's a place that I, as a student of ancient Indian architecture, will carry with me, etched in my memory, for years to come.

Birla Mandir Hyderabad

Perched atop Kala Pahad, the Birla Mandir in Hyderabad presents a striking vision in white marble, a modern interpretation of traditional Nagara architecture ([1][2]). Commissioned by the Birla family and completed in 1966, this temple dedicated to Lord Venkateswara offers a serene counterpoint to the bustling city below ([3]). Its design prioritizes simplicity and elegance, diverging from the elaborate carvings found in some ancient North Indian temples ([4]). Stone platforms and foundations demonstrate a commitment to enduring construction, using granite and red sandstone ([5]). The towering Shikhara (spire), a prominent feature, draws inspiration from the Orissan style of temple architecture, dominating the Hyderabad skyline ([1][3]). Inside the Garbhagriha (sanctum), the Venkateswara deity inspires devotion, modeled after the revered icon at Tirupati ([2]). The temple maintains a tranquil atmosphere, intentionally avoiding the use of bells to encourage quiet reflection ([4]). Intricate carvings adorning the walls narrate stories from the Mahabharata and Ramayana, linking the temple to India's rich epics ([5]). While specific textual references are not documented for this modern structure, Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, may have influenced the temple's orientation and layout ([1]). During the modern period, temple architecture saw a resurgence of traditional styles adapted to contemporary materials and construction techniques ([2][3]). This temple welcomes visitors of all faiths, reflecting India's inclusive spiritual heritage ([4]). The Birla Mandir stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of Indian architectural traditions in the modern era ([5]).

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides