Has Inheritage Foundation supported you today?

Your contribution helps preserve India's ancient temples, languages, and cultural heritage. Every rupee makes a difference.

Secure payment • Instant 80G certificate

Sri Krishna Temple Udupi

The scent of incense hung heavy in the air, a fragrant welcome to the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha. Sunlight glinted off the ornate copper roof of the main temple, a vibrant splash of colour against the otherwise muted ochre walls. As a travel blogger who has traversed the length and breadth of India, documenting every UNESCO World Heritage site, I can confidently say that Udupi holds a unique charm, a spiritual resonance that sets it apart. It's not a UNESCO site itself, but its cultural and historical significance, deeply intertwined with the Dvaita philosophy of Madhvacharya, makes it a must-visit for anyone exploring India's rich heritage. Unlike the towering gopurams that dominate South Indian temple architecture, the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha is characterized by its relative simplicity. The exterior walls, while adorned with intricate carvings, maintain a sense of understated elegance. The real magic, however, lies within. One doesn't enter the sanctum sanctorum directly. Instead, devotees and visitors alike get a unique darshan of Lord Krishna through a small, intricately carved window called the "Kanakana Kindi." This nine-holed window, plated with silver, offers a glimpse of the deity, a tradition established by Madhvacharya himself. It's a powerful moment, a connection forged through a small aperture, yet brimming with spiritual significance. My visit coincided with the evening aarti, and the atmosphere was electrifying. The rhythmic chanting of Vedic hymns, the clang of cymbals, and the aroma of camphor filled the air, creating an immersive sensory experience. The courtyard, usually bustling with activity, fell silent as devotees lost themselves in prayer. Observing the rituals, the deep devotion etched on the faces of the worshippers, I felt a palpable sense of connection to centuries of tradition. The temple complex is more than just the main shrine. A network of smaller shrines dedicated to various deities, including Hanuman and Garuda, dot the premises. Each shrine has its own unique architectural style and historical narrative, adding layers of complexity to the overall experience. I spent hours exploring these smaller temples, each a testament to the rich tapestry of Hindu mythology. The intricate carvings on the pillars, depicting scenes from the epics, are a visual treat, showcasing the skill and artistry of the craftsmen who shaped this sacred space. One of the most striking features of the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha is the "Ashta Mathas," eight monasteries established by Madhvacharya. These Mathas, located around the main temple, play a crucial role in preserving and propagating the Dvaita philosophy. Each Matha has its own unique traditions and rituals, adding to the diversity of the religious landscape. I had the opportunity to interact with some of the resident scholars, and their insights into the philosophical underpinnings of the temple and its traditions were truly enlightening. Beyond the spiritual and architectural aspects, the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha also plays a significant role in the social and cultural fabric of the region. The temple kitchen, known for its delicious and hygienic meals, serves thousands of devotees every day. Witnessing the organized chaos of the kitchen, the sheer scale of the operation, was an experience in itself. It's a testament to the temple's commitment to serving the community, a tradition that has been upheld for centuries. Leaving the Udupi Sri Krishna Matha, I felt a sense of peace and fulfillment. It's a place where history, spirituality, and culture converge, creating an experience that is both enriching and transformative. While it may not yet bear the official UNESCO designation, its cultural significance is undeniable. It’s a testament to the enduring power of faith and tradition, a place that deserves to be on every traveller's itinerary.

Chausath Yogini Temple Jabalpur

Perched atop a hill in Bhedaghat, Jabalpur, the Chausath Yogini Temple presents a captivating silhouette ([1]). Constructed around 950 CE by the Kalachuri dynasty, this open-air, circular temple deviates from conventional temple architecture ([2]). Dedicated to the sixty-four Yoginis, female attendants of Durga, the temple embodies a unique spiritual and architectural heritage ([3]). Granite and sandstone blocks, meticulously carved, form the structure of this hypostyle marvel ([4]). The Pratihara architectural style is evident in its design, reflecting the artistic preferences of the Kalachuri period ([5]). Unlike typical towering structures, its raw, primal energy emanates from the weathered stone and the powerful presence of the Yogini sculptures ([1]). Their diverse iconography, from wielding weapons to meditative poses, links to tantric practices ([3]). Walking the circular ambulatory offers panoramic views of the Narmada river ([1]). Within the Garbhagriha (Sanctum), a small shrine dedicated to Lord Shiva reinforces his supreme position ([2]). The temple's stark simplicity, devoid of excessive ornamentation, emphasizes the natural beauty of the sandstone and its dramatic setting ([4]). This unique temple exemplifies the ingenuity and artistic vision of the Kalachuri dynasty ([5]). During the Kalachuri period, temple architecture in the region saw a flourishing of unique styles ([6]). The Chausath Yogini Temple's circular design is a departure from the more common rectangular or square layouts often dictated by Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture ([7]). This distinctive layout might be connected to tantric traditions, where circular forms symbolize the cyclical nature of existence ([8]). The open colonnaded circle, or hypostyle design, allows for natural light and ventilation, creating a unique spiritual ambiance ([9]). This temple stands as a testament to the Kalachuri dynasty's artistic vision and their patronage of innovative architectural forms ([10]).

Koneswaram Temple Trincomalee Sri Lanka

Koneswaram Temple, dramatically perched atop the majestic Swami Rock overlooking the azure waters of the Indian Ocean in Trincomalee, represents one of the most extraordinary and spiritually significant Hindu temples in South Asia, with origins tracing back to the 3rd century BCE and serving as one of the five ancient Pancha Ishwaram shrines dedicated to Shiva that were strategically established around the island's coastline to protect Sri Lanka according to ancient Tamil and Sanskrit traditions, creating a powerful testament to the profound transmission of Indian Shaivite religious and architectural traditions to Sri Lanka. The temple complex, known as Thirukoneswaram in Tamil and Koneswaram Kovil, features sophisticated Dravidian architectural elements that demonstrate the direct transmission of South Indian temple architecture, particularly the traditions of the Pallava, Chola, and Pandya dynasties, with local adaptations that reflect the sophisticated synthesis of Indian Shaivite religious and artistic traditions with Sri Lankan building techniques and aesthetic sensibilities. The temple's most remarkable feature is its spectacular location atop Swami Rock, a dramatic promontory that rises 400 feet above sea level, providing panoramic views of the Indian Ocean and Trincomalee Bay, while the temple's architectural layout, with its central sanctum housing the Shiva lingam surrounded by multiple enclosures, gopurams (gateway towers), and subsidiary shrines, follows sophisticated South Indian Dravidian temple planning principles that were systematically transmitted from the great temple complexes of Tamil Nadu including Chidambaram, Madurai, and Rameswaram. Archaeological evidence reveals that the temple served as a major center of Shaivite worship for over two millennia, attracting pilgrims from across South India and Southeast Asia, while the discovery of numerous inscriptions in Tamil, Sanskrit, and Sinhala provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian religious texts and practices to Sri Lanka, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian Shaivite traditions possessed by the temple's patrons and religious establishment. The temple's history is deeply intertwined with the Ramayana epic, with local traditions identifying the site as one of the places where Ravana, the legendary king of Lanka, worshipped Shiva, while the temple's association with the Pancha Ishwaram network demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian Shaivite cosmology and temple planning principles that were transmitted from the great religious centers of India to Sri Lanka. The temple complex has undergone multiple reconstructions throughout its history, most notably after its destruction by Portuguese colonizers in 1624 CE, with the current structure representing a modern reconstruction that faithfully preserves the temple's original Dravidian architectural character and spiritual significance. Today, Koneswaram Temple stands as one of the most important Hindu pilgrimage sites in Sri Lanka, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian Shaivite culture and architecture to Sri Lanka, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Sri Lankan religious and artistic traditions. ([1][2])

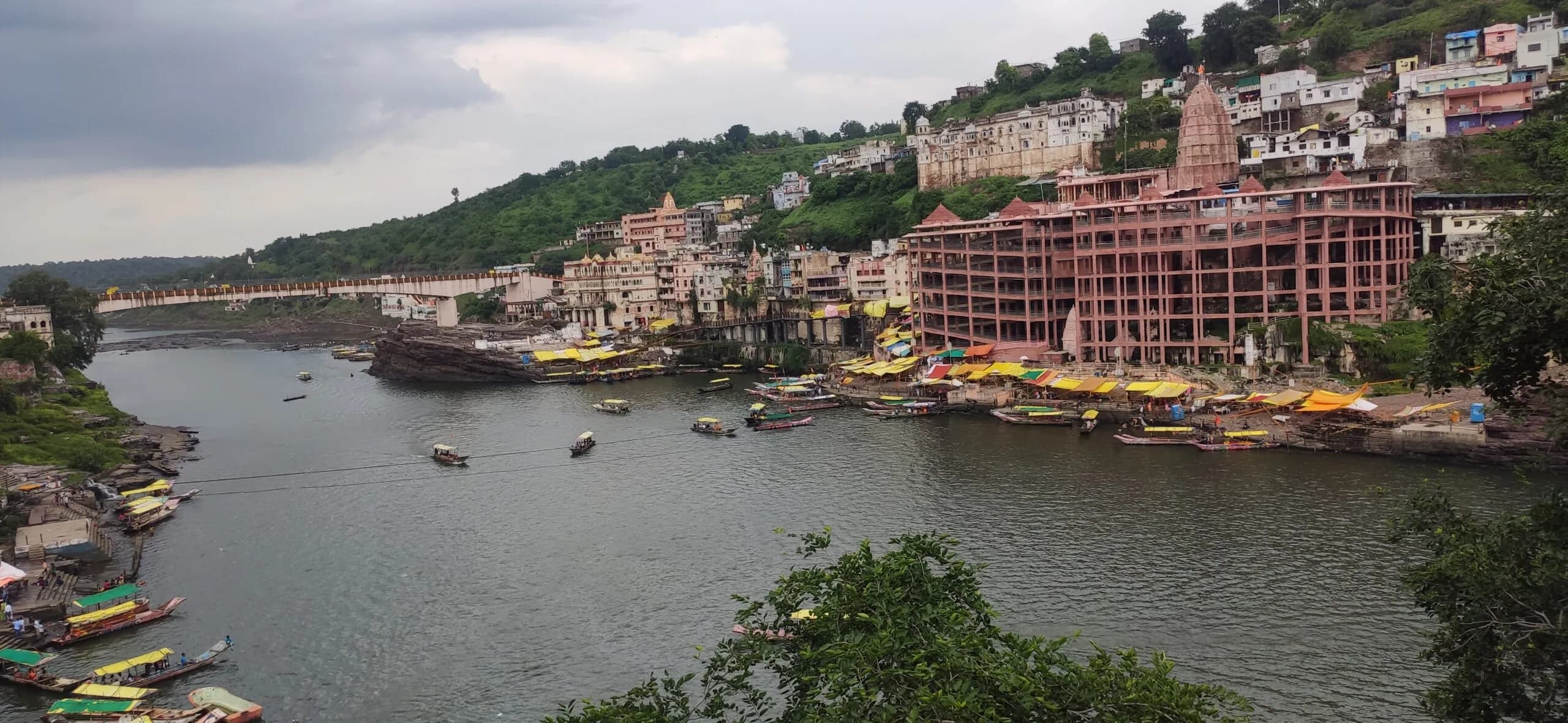

Omkareshwar Temple Mandhata

The Narmada, a river revered as much as the Ganga in these parts, cradles a sacred isle shaped like the sacred syllable 'Om'. This island, Mandhata, houses the revered Omkareshwar Temple, a place I, as a cultural journalist steeped in the traditions of Uttar Pradesh, felt compelled to experience. The journey from the ghats of Varanasi to the banks of the Narmada felt like traversing the spiritual heart of India. Crossing the Narmada on a small boat, the temple’s white shikharas rose before me, gleaming against the deep blue sky. The structure, primarily built of sandstone, displays the quintessential Nagara style of North Indian temple architecture, a familiar sight to someone accustomed to the temples of UP. However, the setting, perched atop the rocky island amidst the swirling waters, lent it a unique aura, distinct from the plains-based temples I knew. The main shrine, dedicated to Lord Shiva as Omkareshwar (Lord of Om Sound), is a compact but powerful space. The sanctum sanctorum, dimly lit, emanated a palpable sense of sanctity. The lingam, the symbolic representation of Shiva, is naturally formed and not carved, adding to the sacredness of the place. The priest, with his forehead smeared with ash, performed the rituals with a practiced ease, chanting Sanskrit shlokas that resonated through the chamber. The air was thick with the scent of incense and the murmur of devotees. Unlike the sprawling temple complexes of Uttar Pradesh, Omkareshwar Temple felt more intimate. The circumambulatory path around the main shrine offered breathtaking views of the Narmada and the surrounding Vindhya ranges. The carvings on the outer walls, though weathered by time and the elements, still bore testament to the skill of the artisans who crafted them centuries ago. I noticed depictions of various deities, scenes from Hindu mythology, and intricate floral patterns, a visual narrative of faith and devotion. One striking feature that caught my attention was the presence of two garbhagrihas, a rarity in North Indian temples. While the main sanctum houses the Omkareshwar lingam, the other, slightly smaller one, is dedicated to Amareshwar, believed to be the brother of Omkareshwar. This duality, a reflection of the complementary forces of the universe, added another layer of symbolic significance to the temple. Beyond the main temple, the island itself is a place of pilgrimage. Narrow lanes lined with shops selling religious paraphernalia and local handicrafts wind their way through the small town. The vibrant colours of the sarees, the aroma of freshly prepared prasad, and the constant hum of chanting created a sensory overload, a stark contrast to the quiet serenity of the temple’s inner sanctum. As I sat on the ghats, watching the sun dip below the horizon, painting the sky in hues of orange and purple, I reflected on the journey. While the architectural style of Omkareshwar Temple resonated with the familiar forms of my home state, the unique geographical setting and the palpable spiritual energy imbued it with a distinct character. It was a powerful reminder of the diverse expressions of faith and devotion that thread together the cultural tapestry of India. The Narmada, flowing ceaselessly, seemed to carry the whispers of ancient prayers, echoing the timeless reverence for the divine. The experience was not merely a visit to a temple; it was a pilgrimage into the heart of India's spiritual landscape.

Bekal Fort Kasaragod

Amidst Kerala's coastal tapestry lies Bekal Fort, a 17th-century sentinel erected by Shivappa Nayaka of Keladi around 1650 CE ([3][4]). Unlike the Mughal's northern citadels, Bekal Fort showcases Kerala's military architecture, strategically positioned along the Malabar Coast ([1][4]). Its laterite walls, stretching over a kilometer, embody raw, earthy strength, a testament to the region's defensive needs ([1][2]). Sophisticated strategic planning defines Bekal Fort, evident in its keyhole-shaped bastion offering panoramic maritime views ([3]). The zigzagging pathways, a deliberate design to disorient invaders, highlight the fort's military function ([4]). The fort's design integrates Kerala's architectural traditions, reflecting the region's unique aesthetic sensibilities ([2]). While lacking the ornate carvings of other Indian forts, Bekal's beauty resides in its stark simplicity, emphasizing the natural strength of laterite ([1][2][5]). Within the fort's expanse, a Hanuman temple provides a vibrant counterpoint to the muted tones of the laterite structure ([3]). This sacred space reflects the enduring Hindu traditions of the region, coexisting harmoniously within the fort's military architecture. Vastu Shastra principles, the ancient Indian science of architecture, likely influenced the fort's layout, optimizing its defensive capabilities and aligning it with natural energies, though specific textual references are not available ([2]). Bekal Fort stands as a powerful reminder of Kerala's rich history and architectural prowess, blending military strategy with regional artistry ([4][5]). Laterite, stone, wood, and clay were used in the construction of this fort ([2]).

Suket Palace Sundernagar

The crisp mountain air of Sundernagar carried the scent of pine as I approached Suket Palace. Nestled amidst the verdant slopes of the Himachal Pradesh valley, this former royal residence, though not imposing in the scale I'm accustomed to seeing in South Indian temple complexes, possessed a quiet dignity. Its relatively modest size, compared to, say, the Brihadeeswarar Temple, belied the rich history it held within its walls. Built in a blend of colonial and indigenous hill architectural styles, it presented a fascinating departure from the Dravidian architecture I've spent years studying. The palace’s cream-colored façade, punctuated by dark wood balconies and intricately carved window frames, stood in stark contrast to the vibrant hues of gopurams back home. The sloping slate roof, a practical necessity in this snowy region, was a far cry from the towering vimanas of Southern temples. This adaptation to the local climate and available materials was a recurring theme I observed throughout my visit. The use of locally sourced wood, both for structural elements and decorative carvings, spoke to a sustainable building practice that resonated deeply with the traditional construction methods employed in ancient South Indian temples. Stepping inside, I was struck by the relative simplicity of the interiors. While lacking the opulent ornamentation of some Rajput palaces, Suket Palace exuded a sense of understated elegance. The spacious rooms, with their high ceilings and large windows, offered breathtaking views of the surrounding valley. The wooden floors, polished smooth by time and countless footsteps, creaked softly under my feet, whispering stories of bygone eras. I was particularly drawn to the intricate woodwork adorning the doors, window frames, and ceilings. The patterns, while distinct from the elaborate sculptures found in South Indian temples, displayed a similar level of craftsmanship and attention to detail. Floral motifs, geometric designs, and depictions of local flora and fauna intertwined to create a visual narrative unique to this region. One room, converted into a museum, housed a collection of royal artifacts, including portraits of past rulers, antique furniture, and weaponry. These objects offered a glimpse into the lives of the Suket dynasty and the cultural influences that shaped their reign. The portraits, in particular, were fascinating. The regal attire and stoic expressions of the rulers provided a stark contrast to the more stylized and often deified representations of royalty found in South Indian temple art. The palace gardens, though not as expansive as the temple gardens I'm familiar with, were meticulously maintained. Terraced flowerbeds, brimming with colorful blooms, cascaded down the hillside, creating a vibrant tapestry against the backdrop of the towering Himalayas. The integration of the natural landscape into the palace design reminded me of the sacred groves that often surround South Indian temples, highlighting the reverence for nature that transcends geographical boundaries. As I wandered through the palace grounds, I couldn't help but draw parallels between the architectural traditions of the north and south. While the styles and materials differed significantly, the underlying principles of functionality, aesthetics, and spiritual significance remained remarkably similar. The use of local materials, the adaptation to the climate, and the incorporation of symbolic motifs were all testament to the ingenuity and artistry of the builders, regardless of their geographical location. Suket Palace, in its own unique way, echoed the same reverence for history, culture, and craftsmanship that I've always admired in the grand temples of South India. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that architectural marvels can be found in the most unexpected places, each whispering its own unique story of the people and the land that shaped it.

Prasat Sikhoraphum Surin

Prasat Sikhoraphum, located in Sikhoraphum District of Surin Province, represents a significant 12th-century Khmer Hindu sanctuary distinguished by its five brick prasats arranged in a quincunx pattern and exceptional preservation of original stucco decorations. The temple complex, constructed during the reign of Suryavarman II (1113-1150 CE) in the Angkor Wat period, is dedicated to Shiva, with the central tower housing a massive lingam pedestal and the four corner towers containing smaller shrines. The complex spans approximately 2 hectares and features a rectangular laterite enclosure wall measuring 42 by 57 meters, accessed through a single eastern gopura that leads to the inner courtyard. The five prasats, constructed primarily from brick with sandstone doorframes and lintels, rise to heights between 12 and 15 meters, with the central tower being the tallest. The temple’s most remarkable feature is its extensive stucco decoration, which covers the brick surfaces with intricate bas-relief work depicting Hindu deities, celestial dancers, and mythological scenes—a rarity in Khmer architecture where most stucco has been lost to weathering. The stucco work includes depictions of Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, and various devatas, executed with exceptional skill and preserving details of clothing, jewelry, and facial expressions. The temple’s lintels, carved from sandstone, depict scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, with particular emphasis on Krishna’s exploits. The complex includes two libraries positioned east of the central prasat, numerous subsidiary shrines, and evidence of a sophisticated drainage system. Archaeological evidence indicates the temple served as a regional religious center for the Khmer Empire’s control over the Mun River valley. The site underwent restoration from 1987 to 1995, involving structural stabilization, stucco conservation, and reconstruction of collapsed elements. Today, Prasat Sikhoraphum remains an important site for understanding Khmer stucco art and brick construction techniques, attracting visitors interested in its exceptional decorative preservation and architectural significance. ([1][2])

Ita Fort Itanagar

The midday sun cast long shadows across the undulating hills surrounding Itanagar, highlighting the weathered brick-red ramparts of the Ita Fort. Ascending the gentle slope towards the main entrance, I felt a palpable shift in atmosphere, a sense of stepping back in time. This wasn't merely a historical site; it was a living testament to the architectural ingenuity of the Tai-Ahom people who once ruled this region. Ita Fort, also known as the Ita Krung, isn't a fort in the conventional sense of a singular fortified structure. It's more accurately described as a fortified complex, a sprawling network of ramparts, gateways, and earthen mounds enclosing a vast area. The walls, constructed primarily of bricks, are remarkable for their sheer size and the irregular, almost organic way they follow the contours of the land. Unlike the precisely measured and geometric fortifications of the Mughals, Ita Fort displays a different kind of sophistication – an understanding of the landscape and its defensive potential. Passing through the main gateway, a modest arched opening in the thick walls, I found myself in a large open space. Here, the remnants of several structures were visible – low brick platforms, scattered fragments of walls, and the intriguing circular depressions that are believed to have been the bases of granaries. The absence of elaborate ornamentation or intricate carvings was striking. The beauty of Ita Fort lies in its stark simplicity, its functional design, and the sheer scale of the undertaking. The bricks themselves are a story. Large and uneven, they bear the marks of hand-crafting, a tangible connection to the builders who labored centuries ago. The mortar, a mixture of clay and organic materials, has weathered over time, giving the walls a textured, almost tapestry-like appearance. I ran my hand over the rough surface, imagining the hands that had placed these very bricks, the generations who had sought shelter within these walls. Climbing to the highest point of the ramparts, I was rewarded with a panoramic view of the surrounding hills and the valley below. It was easy to see why this location was chosen for the fort. The elevated position provided a clear line of sight for miles, allowing the inhabitants to monitor the approaches and defend against potential invaders. The strategic importance of Ita Fort was undeniable. One of the most fascinating aspects of Ita Fort is the mystery surrounding its precise history. While it is generally attributed to the Tai-Ahom kingdom, the exact date of construction and the details of its use remain shrouded in some ambiguity. Local legends and oral traditions offer glimpses into the fort's past, but concrete archaeological evidence is still being unearthed. This air of mystery adds another layer to the experience, a sense of engaging with a puzzle whose pieces are slowly being revealed. As I descended from the ramparts, the late afternoon sun cast a golden glow over the ancient bricks. Ita Fort is more than just a collection of ruins; it's a portal to a vanished era, a reminder of the rich and complex history of this region. It's a place where the whispers of the past mingle with the sounds of the present, offering a unique and deeply rewarding experience for anyone willing to listen. It’s a site that deserves greater attention, not just for its architectural significance but also for the stories it holds within its weathered walls. My visit left me with a profound sense of awe and a renewed appreciation for the ingenuity and resilience of those who came before us.

Sri Aruloli Thirumurugan Temple Penang Hill

Sri Aruloli Thirumurugan Temple, founded in the 1800s by Tamils working on the Penang Hill funicular rail, sits 833 metres above sea level and is among Malaysia’s oldest hilltop Hindu shrines, offering panoramic views of George Town while housing Murugan with Valli-Deivanayai in a granite sanctum rejuvenated in 2016 with a colourful rajagopuram inspired by Palani ([1][2]). The temple opens 6:00 AM-9:00 PM providing daily puja, hilltop meditation, and annadhanam from a vegetarian kitchen that uses hydroponic produce grown on terraces. The Penang Hill funicular transports pilgrims, who ascend a final flight of steps to the mandapa framed by manicured gardens and temperature-controlled sanctum housing brass vel, peacock icons, and murals of Murugan’s mythical battles. Penang Hill Corporation, temple trustees, and volunteer rangers manage sustainability: rainwater harvesting, solar panels, waste segregation, and wildlife corridors protect the hill’s rainforest. Thaipusam sees kavadi carriers trek up after the city procession; Skanda Shasti and Thai Pusam attract 15,000 visitors annually, supported by volunteer medics, mountain rescue, and crowd monitoring integrated with Penang Hill’s operations centre. The temple doubles as a cultural interpretation node for Penang Hill UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, offering eco-pilgrim briefings and heritage storytelling ([1][3]).

Mehter Tepe Balkan Turkmenistan

Mehter Tepe, a sanctuary located in the Balkan Region of Turkmenistan, stands as a testament to the profound and continuous cultural exchanges that have shaped India's millennia-spanning heritage, particularly through its Indo-Parthian architectural style [1] [2]. While geographically situated in Central Asia, the site embodies an architectural fusion that integrated Greek, Persian, and notably, Indian styles, reflecting a deep historical continuum of artistic and cultural interaction [1] [3]. The construction primarily utilized indigenous materials such as mud brick, baked brick, and stone, often finished with plaster and stucco, characteristic of the Parthian period's robust building practices [5] . These materials were employed in sophisticated construction techniques, including the development of vaults and domes, which became defining features of the broader Parthian architectural tradition . The site's design likely incorporated elements such as monumental iwans, a distinctive architectural feature of Parthian and later Iranian architecture, which may have been adapted to local religious or ceremonial functions . Although specific dimensions for Mehter Tepe are not widely documented, Indo-Parthian structures typically featured substantial courtyards, columned halls, and intricate decorative elements that showcased a blend of Hellenistic and indigenous motifs [1] [4]. Carvings and sculptures, if present, would likely exhibit the syncretic artistic expressions of the Indo-Parthian realm, where Gandharan art, with its strong Indian Buddhist influences, flourished [1] [4]. The structural systems would have relied on thick load-bearing walls and the innovative use of arches and barrel vaults to create expansive interior spaces, demonstrating advanced engineering for its time [5] . Water management systems, crucial in arid regions, would have involved cisterns or qanats to ensure sustainability, while defensive features, such as fortified walls, might have been integrated given the geopolitical context of the Parthian Empire [5]. Currently, Mehter Tepe is reported to be on the UNESCO Tentative List, signifying its recognized universal value and the potential for future inscription as a World Heritage Site [2] [3]. Archaeological findings in the broader Indo-Parthian regions, such as those by Sir John Marshall in India, have unearthed numerous Parthian-style artifacts, providing context for understanding sites like Mehter Tepe [4]. Conservation efforts would focus on preserving the integrity of the mud-brick and stone structures, mitigating erosion, and stabilizing extant architectural elements, ensuring the site's enduring legacy [5]. The site's operational readiness would involve ongoing archaeological research, site management, and the development of visitor infrastructure to facilitate accessibility and interpretation, celebrating its role in the continuous tradition of Indian civilization [4].

Koneurgench Dash Mosque Temple Remnants Dashoguz Turkmenistan

Koneurgench, dramatically situated in the Dashoguz Region of northern Turkmenistan, represents one of the most extraordinary and archaeologically significant medieval cities in Central Asia, serving as the capital of the Khorezm Empire and featuring the remarkable Dash Mosque with its 12th-13th century temple remnants that demonstrate pre-Islamic layers with remarkable parallels to Indian religious and architectural traditions, creating a powerful testament to the sophisticated synthesis of Indian and Central Asian cultural traditions during the medieval period. The ancient city, also known as Kunya-Urgench and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, features extraordinary architectural elements including the Dash Mosque with its underlying temple structures that demonstrate clear Indian architectural influences from periods before the Islamic conquest, while the site's most remarkable feature is its sophisticated pre-Islamic temple remnants featuring architectural elements, ritual structures, and decorative programs that demonstrate clear parallels with Indian temple architecture and religious practices. The temple remnants' architectural layout, with their central ritual structures surrounded by ceremonial spaces and architectural elements, follows sophisticated planning principles that demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian temple planning principles, while the temple remnants' extensive decorative programs including architectural elements and religious iconography demonstrate the sophisticated synthesis of Indian religious iconography and architectural traditions with local Central Asian aesthetic sensibilities. Archaeological evidence reveals that the site served as a major center of religious and cultural activity for centuries before the Islamic period, attracting traders, priests, and elites from across Central Asia, South Asia, and beyond, while the discovery of numerous artifacts including architectural elements that demonstrate clear Indian influences, ritual objects that parallel Indian practices, and religious iconography that reflects Indian cosmological concepts provides crucial evidence of the site's role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to Central Asia, demonstrating the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious and architectural traditions possessed by the site's patrons and religious establishment. The site's association with the Khorezm Empire, which had extensive trade and cultural connections with India throughout its history, demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of Indian religious traditions that were transmitted to Central Asia, while the site's pre-Islamic temple remnants and architectural elements demonstrate remarkable parallels with Indian temple architecture and religious practices that were central to ancient Indian religious traditions. The site has been the subject of extensive archaeological research, with ongoing excavations continuing to reveal new insights into the site's sophisticated architecture, religious practices, and its role in the transmission of Indian religious traditions to Central Asia, while the site's status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site demonstrates its significance as a major center for the transmission of Indian cultural traditions to Central Asia. Today, Koneurgench stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and represents one of the most important medieval cities in Central Asia, serving as a powerful testament to the transmission of Indian religious and architectural traditions to Central Asia, while ongoing archaeological research and conservation efforts continue to protect and study this extraordinary cultural treasure that demonstrates the profound impact of Indian civilization on Central Asian religious and cultural traditions. ([1][2])

Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple Aranmula

Enclosed by Kerala's lush landscapes, the Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple, a shrine dedicated to Lord Krishna, exemplifies the region's distinct architectural heritage ([1][2]). Constructed around 1550 CE, during the Chera period, the temple diverges from the towering gopurams (gateway towers) typical of Tamil Nadu temples, embracing the Kerala style with its sloping, copper-shingled roofs ([3][4]). Commissioned by Pandya Dynasty kings, the temple showcases the architectural prowess of the time ([5]). Intricate carvings embellishing the wooden eaves and pillars narrate scenes from the Mahabharata, reflecting the region's deep-rooted mythological traditions ([1][2]). The use of laterite, wood, stone, and copper highlights the traditional materials employed in Kerala temple construction ([3][4][5]). Further, the Koothambalam (temple theatre) within the complex underscores the temple's function as a cultural center, its ornate pillars resonating with the echoes of Kathakali performances ([1][2]). Within the Garbhagriha (Sanctum Sanctorum), the deity is adorned with resplendent silks and jewels, creating a mystical ambiance heightened by the aroma of sandalwood and incense ([3][4]). The temple's design may subtly align with principles outlined in texts like the *Manasara Shilpa Shastra*, though specific verses are not directly documented ([5]). Also, Aranmula's connection to the Aranmula Kannadi, a unique metal mirror crafted through a secret process, adds to the temple's mystique ([1][2][3]). During the annual Onam festival, the Vallam Kali boat race on the Pampa River enhances the temple's spiritual significance, celebrating the enduring power of tradition ([4][5]). The temple stands as a repository of Kerala's cultural and architectural legacy, inviting visitors to immerse themselves in its rich history and spiritual aura ([1][2][3]). The gable roofs further accentuate the distinctiveness of the temple, setting it apart from other architectural styles in the region ([4][5]).

Quick Links

Plan Your Heritage Journey

Get personalized recommendations and detailed visitor guides